Just How Bad were Marc Trestman’s Bears? (Pt. II)

A longform exploration of a crucial period.

Exordium

Come in. Have a cigar. Fix yourself a drink, and rest a spell, if you please. It’s been a while.

In the early months of 2020, I wrote an article titled “Just How Bad were Marc Trestman’s Bears?”, adding with an eye towards my surely glorious future as a longform sportswriter the untactfully ambitious subheading “Pt. I.” In the article, I closed my writing with some smug valediction about what I would be covering in the surely soon-to-be-written-and-released “Pt. II,” which would necessarily be the foreshortened domanial mismanagement of the Bears, and specifically the Bears defense, by transplant CFL coach (though a United States national by birth from the timberline of Minnesota) Marc Trestman. I say “necessarily” because, even though I had assigned the title “Just How Bad were Marc Trestman’s Bears” to this article, not a syllable of sportswriting was spent in scrutiny of either the 2013 or 2014 Chicago Bears seasons – the two years during which Marc Trestman was Bears HC.

This caused a paradox. True, I *did* intend to actually explain Just How Bad Marc Trestman’s Bears Were, in Pt. II – but Pt. II never appeared. Thus the first piece, “Pt. I,” well-intentioned though its title was, was misleading in the extreme. The piece did drive at the coming diluvial ineptitude authored by these Bears, so it wasn’t an unabsolvable falsity of terms, but it wasn’t exactly, well, accurate to what was promised in the headlining. But Pt. II never came about, its central question never investigated, its upshot never gotten around to. It was a half-composed concerto, a semi-devised disquisition, an opusculum in want of becoming an opus unto itself. And at times, I felt the haunting call of the incompleteness of this work nipping intermittently at me, jabbing me in times of idle reflection with the thought of a promise broken – even if the promise was primarily one made to myself and not an imaginary panoply of eager readers, which, as far as my site’s traffic indicates, has yet to manifest itself. Every so often I’d be reminded of that man, Marc Trestman, the guy who cut such a different figure compared to other rock-ribbed, square-jawed, manifestly meatheaded NFL head coaches’ physiques and physiognomies. The notion of the man would pop up now and again, both in my mind and in the news. He was briefly the head coach of the XFL’s Tampa Bay Vipers, a league and a team so ill-fatedly timed in their resurrection as to be almost comical on the world football stage; he features as a bit-part player in the 1985-focused episode of the amazing NFL Films series Caught In The Draft, uploaded to YouTube in 2021, during which he in his capacity as Minnesota Vikings RB coach desperately attempts an abortive recruiting endeavor of Miami’s Bernie Kosar, who he had been QB coach for in 1983 and ’84, which is an interesting-enough story to warrant its own, independent telling; he became increasingly invoked as the palpably maladroit spiritual predecessor to Matt Nagy, whose incapacity as an offensive mastermind eerily mirrored those of Trestman, though the latter differentiated his own personal blend of offensive shortcoming with perhaps more invidious conflictions between himself and the media; and just last offseason, he returned somewhat quietly to the NFL, joining on with Jim Harbaugh’s Los Angeles Chargers in the role of Senior Offensive Assistant, a move, though in no doubt not inconsequential, that probably was not intended as the sort of publicity stunt meant to quiet Harbaugh’s detractors who thought he might not be the right guy to maximize Justin Herbert.

I thought little of Marc Trestman otherwise. One does not do well to dwell on the obscure underachievements of a decade-old coaching stint which, though interesting to some, is forgotten by almost everyone who watches football casually, and is not memorialized very sharply by even the keenest football historians. Nor was it all that possible; even if I had gotten around to penning the second, climactic, finality-sodden chapter of the Just How Bad piece later in 2020, there could not have been much more excogitation on the topic besides. I mean, there’s only 32 games worth of stuff here to analyze – how much can someone possibly ponder Marc Trestman, especially when there are other things far worthier of the courtesy of one’s contemplation? The answer is, clearly, not very much, notwithstanding one’s attempts.

But the reason Marc Trestman’s Bears were not accorded their sworn examination is due in small, almost negligible part to the subject matter’s self-evident insignificance comparative to the world at large or even to other NFL contemporary affairs. Rather, it is due almost wholly to my inability to continue down the path of the scribbling sportswrite at the same time that my life was changing from adolescence to adulthood. Sure, I was technically already a man by the time I published that first piece in 2020 (I was 23, a recent college graduate and not living at home), but I was not a fully-fledged professional worker bee, not an “employee” in any substantive sense. To be clear: I didn’t have a job. Well, sort of – I had something going, fairly cushy, while I was looking for a long-term job – but that didn’t really count. I didn’t have the weighty, cumbersome strain of responsibilities that would come with being a salaried 9-to-5 type guy who gets the pleasure of worrying, fretting, stressing, fearing, and despairing over the obligations of a job. In short, I had not collected and assembled all the clockwork of what the “expectation” of an American in the workforce called for. I was not living in financial freedom and I was without a clear path forward. In a way, the recognition of this liminal state allowed for my diversion in sportswriting to first blossom; it is amazing how productive you can be at something other than applying for jobs when your number one, most solemn and gravest priority is applying for jobs, and in my turn I channeled a surplus volume of motivation that could maybe have been better spent on careerist exploration into instead delving into the microscopy and minutiae of an NFL team whose defense had been my first and most indelible teachers of what fantasy football trauma is all about.

After COVID-19 began to spread across the world I moved back home. This allowed me time to focus even more than before on football writing, but still the drive, interest, and desire to finish the semi-engaging story of Marc Trestman and his sorry team eluded me. I reflect now a bit on what made me so interested in this story, and I find that I can pinpoint a single, crystallized, cynosural moment that captured my intrigue about this weird, backwards, defensively discommodious outfit. Take a whirl with me even further into the past.

Borrowed from the German TV show Dark, which is a fitting name to affix to any discussion of recent Bears history.

Ent’racte

When we think of bad defenses, our minds tend to wander towards the most well-known and notorious of the lot. There’s last year’s Panthers, who surrendered the most points ever in a season (over 17 games, the most any team’s ever played in a regular season, of course); there’s the 1981 Baltimore Colts, whose record those Panthers broke, who surrendered 533 in 16, the worst mark ever for a 16-game season, and a team we could describe as “deeply unserious” in 2020s argot; there’s the 2008 Detroit Lions, losers of all 16 games they played; and there’s the 1966 New York Giants, a team that played (on the losing end, of course) in the highest-scoring game in NFL history, and who also surrendered 47 or more points five times in a single season. In 1966.

These are the teams that are bad in absolute terms. They were godawful start to finish, no qualifications or caveats required to explain their heinousness. But their protective film of feebleness shields other, perhaps more subtly sickening defenses from the blazing scrutiny of football heads. And once we move past the simulacra of the most notably grotesque defensive units from the terra cotta army of defenses past, we can examine with more nuance the badness so artfully concealed by the infamy of better-known botch jobs. One such team is Marc Trestman’s Bears.

__________

Part Two:

Marc

__________

The Two-Year Torment, Year 1: From Mice of the Midwest to Microorganisms of Michigan Avenue

The 2012 Bears got rid of their coach of nine years on New Year’s Eve, shortly before the 20-teens launched upon the world. Lovie Smith, you’re fired. We’ve gone over the events leading to the ouster of the only man not named Ditka that was able to bring the Bears to the Super Bowl - late collapses in two successive seasons that saw them tumble unceremoniously from almost certain playoff participation and into the dustbin of What Could Have Been-level teams, notable only to neurotic football historians and aggrieved Illinoisan remembrancers. This team had an issue finishing, it seemed. And they had unmistakable deficiencies on offense - they averaged 14 points in their final 6 games in 2011 and 17 in their final eight in 2012. Change agent, inquire within.

IV. Regime Change: Tresting the Crown

The Bears, not as accustomed to head coaching searches as more volatility-besmitten teams, scoured the class of offensive prospects for head coach. They had elected to either actively or organically fall into the calming momentum of the pendulum-swing of head coach hirings – that is to say, searching for an offensive-minded head coach after spending a spell with a defensive-minded one. Lovie was as defensive-minded as they came, and though his mid-2000’s teams had been piratical, plundering, at times peerless turnover merchants who could regularly score on defense (scoring 7 defensive or special teams touchdowns in 2004, 5 in 2005, then an incredible 8 in 2006, 7 in 2007, and 5 in 2008), those days were long gone by the time he was a heated-seat coach who’d blown back-to-back late season sequences where he’d won at least 70% of his games by the time crunch time rolled around. The defense, which had suffered a hiccup in 2011, was still strong in 2010 (4th in scoring) and 2012 (3rd), but had gone from giving up 15 PPG in the first 8 games of 2012, where the Bears went 7-1, to 20 PPG in the second 8, where they’d gone 3-5. Meanwhile, the offense, which had averaged 30 PPG in the 2012 season’s first half, cratered to just 20 PPG in the second half. As a result, you would have expected the team, which was both scoring and allowing about 20 PPG over the final 8 games, to go 4-4, which would propel them to 11-5 and a certain playoff appearance (as it happened, back-to-back dreadful losses to Seattle and Minnesota in weeks 12 and 13 proved at season’s end to be above the LD50 of permissible losses, as those two teams stole the available Wild Card spots; wins in those games, both one-score heartbreakers, would have altered the fate of the 2012 Chicago Bears from playoff nonparticipants to division champions).

The Bears’ ownership and front office were simply not interested in a defensive-minded head coach, and they insinuated their immense displeasure at the way the preceding seasons had gone by compiling a gigantic list of “candidates” spanning the offensive coordinator, special teams coordinator, and CFL head coach ranks (that’s our boy Marc alone in the third category). And by “gigantic,” I do mean gigantic by NFL standards. They targeted an initial list of 13 names, including their own incumbent special teams coordinator, Dave Toub – which, I mean, c’mon, when has a team ever hired someone from the previous head coach’s staff after they fired the guy and had it work out? The other twelve were Mike McCoy (Broncos OC), Rick Dennison (Texans OC), Mike Sullivan (Buccaneers OC), Peter Carmichael (Saints OC – they probably weren’t interested in the 2012 Saints’ DC), Tom Clements (Packers OC), Darrell Bevell (Seahawks OC, of some notoriety years later), Bruce Arians (Colts OC), Keith Armstrong (Falcons special team coordinator), Joe DeCamillis (Cowboys STC), Mike Priefer (Vikings STC), and finally Marc Trestman, who had coached the Montreal Alouettes since 2008 and won back-to-back Grey Cups in 2009 and 2010. As unorthodox as it would be to hire a coach from the CFL to coach an NFL team, hey – they could do worse. This bloated list of candidates, and the absence of any acting DCs on said list, seems to send quite a message: The Bears were sick of the defensive focus Lovie had preached during his tenure. Offense and scoring would be the focus.

As an aside – would you be amazed to know that, of all the OCs listed above, the one that led the worst scoring offense the previous year was Bruce Arians? With the benefit of hindsight, it seems clear that he would have been very obviously the best choice for the Bears to hire, but the course of NFL history may have been very different – and probably lamer – had he packed his Indianapolis bags and traveled north to the banks of Lake Michigan. Let’s be glad his career as HC flourished the way it did in Arizona and Tampa. It turns out that the Bears missed badly on the Bruce Arians train – but that wasn’t even close to the best possible candidate available in the early months of 2013. The Bears, though they would have been direly pressed for time, declined to speak with Andy Reid. You know, Andy Reid. The guy with the rings. Big Red could have been...Big Blue? The Giants sort of own that title already, so maybe Big Navy? Oversized Orange? It doesn’t matter, it didn’t happen. But it was there for the taking.

Surmising that head coaching experience of any kind trumped whatever offensive or special teams specialists could bring to the dance, the Bears decided to hire Marc Trestman on January 16, 2013, beating out the Cleveland Browns for his services. The Browns and the Bears were the only two teams who interviewed Trestman. The Cleveland Browns of 2012 had also fired their previous head coach, Pat Shurmur, on New Year’s Eve, axing him at the exact same moment in time that Lovie Smith was having his mortal ursine coil shuffled off by the McCaskeys and GM Phil Emery. The Browns took a different tack, hiring Cam Newton’s previous offensive coordinator, Rob Chudzinski, to call plays for...Brandon Weeden?

Relationship with the quarterback would be crucial for Trestman, as Jay Cutler was in the final year of a five-year contract and coming off a deeply disappointing season during which he only threw for 3,033 yards and committed 15 turnovers (with seven other fumbles that his team managed to recover). The Bears needed clarity at the QB position by 2014, and it was hoped that Trestman – who, you’ll remember, so tenaciously and resolutely recruited his quarterback Bernie Kosar ahead of the 1985 Supplemental Draft, as a real guy’s guy – could figure out how to enkindle the flashes of fantastic play that Cutler had shown at points in Denver and on Lovie Smith’s Bears into full-blown inferno.

Unfortunately for Cutler, Trestman, and the Bears, Cutler’s 2013 was cut short by injury, resulting in his starting only 11 games. Despite this, he equaled his touchdown-pass production (19) from the year before by the end of the season despite starting four fewer games. He dramatically reduced the amount of sacks taken, too, halving the times he got dropped in the backfield from 38 in 2012 to 19 in 2013. And it must be said that Cutler began the season as well as any year of his career to that point, setting the Bears franchise record for passing yards through six games.

All you really need to know about the first six games of the Bears’ 2013 season is that they happened and they weren’t particularly notable except for Cutler’s progression as a QB. The biggest immediate improvement for the Bears came in the form of Cutler’s heightened ability to avoid sacks, and the offensive line’s ability to hold up for him better to find a trio of supremely desirable playmakers in Brandon Marshall, Alshon Jeffrey and Martellus Bennett - potentially the best WR1 —> WR2 —> TE combination in the entire NFL in 2013. Yes, really. Having Earl Bennett as a WR3/slot option and the ever-objectionably underrated Matt Forte as a checkdown option made Cutler a very lucky man indeed. They were 3-0 after three games despite surrendering over 20 points in each but then dropped a weird one on the road to Detroit, 40-32, when the Lions scored 27 points in one quarter (the second quarter). Thirteen points in the other three were enough for the Lions to best the Bears, making their quest for an undefeated season a short one. Flukey. Then the Saints traveled to Soldier Field, and in a strange Saints season that saw the Fleur-de-Lis-helmeted defense finish 4th in scoring after finishing 31st in 2012 and dropping back down to 28th in 2014, New Orleans bested Chicago 26-18. 3-2, the Bears were. They got the cupcake Giants next, and even though Eli Manning was well on his way to authoring an abominably munificent season in the realm of turnovers, the Bears were able to merely squeak by the Giants instead of blow them unmercifully out, 27-21. This brought them to a date with RGIII’s Washington Redskins. But let’s hold for a moment.

4-2 going to Washington. Cutler had been more than good enough - no ifs ands or buts about it. He’d passed for 1,630 yards through these six games, an average of 272 per. He’d thrown 12 touchdowns to go along with all these nice yards. If healthy, he’d certainly approach his career mark of 4,526 yards, and would almost surely exceed his touchdown PR of 27. He had thrown 6 interceptions, true, but 3 had come in desperate, comeback-seeking pursuit of Detroit, whose wild performance in Week 4 ensured a haphazard afternoon passing for the Bears QB. It was his first year with a new coordinator, after all, and 4-2 was a great place to be. The defense had clearly not been great - but we’ll come back to them.

As one can see, Cutler was solid. But it was the other Bears QB who was absolutely magnificent. Enter one Josh McCown.

Josh McCown had a fascinating NFL career, and though at the time of this writing he is employed as an NFL coach on the Minnesota Vikings (strange, in fact, that he has not received his “flowers” to anywhere near an equitable level with the Vikes’ head coach, Kevin O’Connell, for the incredible work he performed with The Darnold in 2024), this held true even in 2013. By that time he was a 10-year NFL vet whose most notable action came late in his second year on the Arizona Cardinals, who were mired firmly in their “ocular abomination”-uniform phase where they wore allover-red-printed jerseys with generic white block numerals on them. If you aren’t familiar with these, look below, but be sure to wear some sort of eye protection before gazing upon them:

An old Emmitt Smith, in the very worst finery of his career, receiving a handoff from a young Josh McCown.

His most impressive moment from that 2003 season was easily the ridiculous Hail Mary-esque touchdown he threw to NFL nonentity Nate Pool on the final play of the year, which knocked the Minnesota Vikings out of the playoffs and birthed one of the most threnodial radio calls of all time from play-by-play man par excellence Paul Allen. But McCown was eminently forgettable, bordering on benchable, his remaining years in the desert, throwing 20 touchdowns to 21 interceptions over the following two seasons. He then spent a year on the Detroit Lions in 2006, where he was asked to play wide receiver in a game against the Patriots which also featured Mike Furrey, who himself was a two-way player who occasionally played free safety. Dan Campbell was also on that team. This, after the Lions had drafted wide receivers in the first round in three consecutive drafts between 2003 and 2005. What the hell was going on in Detroit in 2006?

After this McCown signed with the Raiders, where he floundered on an awful Oakland team alongside old nemesis Daunte Culpepper, the guy he’d bounced from the postseason in 2003, before they both gave way to JaMarcus Russell. By 2008-2009, he was backing up Jake Delhomme on the Carolina Panthers, and spent the 2010 season in the United Football League. His career looked over. But he got a second chance (or fifth chance, depending on how you see it) in the NFL with Lovie’s Bears in 2011, where he again threw more interceptions than touchdowns. He saw no action in 2012.

If you’re thinking that it’s unlikely the sixth time would be the charm for a longtime NFL journeyman who had once been asked to switch to wide receiver and had only once, ten years prior in 2004, thrown more touchdowns (11) than interceptions (10), then you’re not alone. McCown threw exactly one pass before halftime after replacing the injured Cutler against Washington in Week 7, assisted by a zero-play offensive scoring drive that saw Devin Hester take a Washington punt to the house and an ultra-long Redskins drive eat up the rest of the half. Despite this, Josh McCown and Matt Forte (mostly Matt Forte, who ran for three touchdowns) led the Bears to 24 second-half points, tying their season-high (they’d already scored 24 points in a half three times before this, somehow) but still ended up falling to a red-hot Washington team, who racked up 45 total points. With 41 points scored, the Bears still lost. That’s only happened 34 times in 105 seasons of NFL play. That’s Marc Trestman’s defense for you. We’ll get back to that side of the ball.

If at this point McCown had been sat down in favor of QB3 Jordan Palmer, it would be one of his best seasons. It would have been only the second time in 12 seasons that he threw more touchdowns (1) than interceptions (0). Going off the sample size, Trestman may have been justified in doing just that. But he stuck with McCown, which proved more fruitful than anyone aside from maybe Josh McCown’s wife could have imagined. The next week, McCown started against Chicago’s hated enemy the Green Bay Packers, where he outgunned overmatched stand-in Seneca Wallace at Lambeau Field, piling up 291 total yards, two passing touchdowns and zero picks for a 90.7 passer rating – only the 13th game of his career he’d eclipsed the 90.0 passer rating mark. Seneca Wallace had a woeful day, throwing for only 114 yards and taking four sacks. Seneca Wallace is no Josh McCown. This game was best remembered, though, for Packers QB Aaron Rodgers lasting even less time in this game than Cutler had the week before, with Rodgers eating a brutal Shea McClellin takedown on the first third down of the game which broke the signal caller’s collarbone. The Bears were better prepared for their QB1 going down than the Packers were.

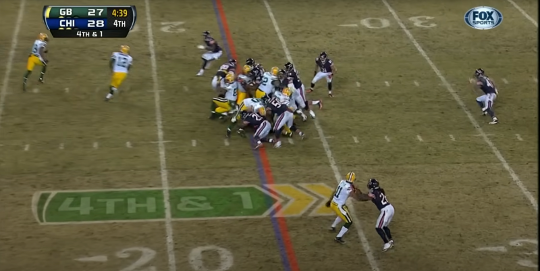

By the midpoint of the season the Bears were 5-3 and caught in a chaotic triskelion atop the NFC North, with their victory over the Bears and a certifiably wild Lions win in Dallas on the preceding day (McCown’s first start had come on MNF) fixing the Lions, Bears and Packers with identical 5-3 records. Poor Minnesota was in the sewer one year after Adrian Peterson’s godlike return from an ACL injury, anguishing in a 1-7 dungeon. The next four games would be torturous for the Bears, though, despite the unexpected and now fully blossoming renaissance of their heroic QB2. They faced those exceptionally fun 2013 Lions the next week back home at Soldier Field, where Cutler made a surprise return to the lineup after a foreshortened recovery from his Washington injury. He played moderately well through three and a half quarters before a Stephen Tulloch hit that wounded the QB’s groin sidelined him yet again, leading to a punt and a potentially game-icing drive from Matthew Stafford that moved the Lions’ lead from 14-13 to 21-13. It was a surprise special episode of The Josh McCown Show for the second time in three games. With 2:28 left, McCown led a Caleb Hanie-like drive off the bench, going 6-for-9 and firing a broken-pocket touchdown strike to Brandon Marshall with seconds left in regulation. Now down 21-19, they needed to go for two. The first attempt, a rollout to the right with Dante Rosario and Matt Forte as the only viable options in an appallingly uninspired playcall, resulted in McCown being gangrushed by the Lions front seven and tossing an incompletion out of the endzone. Willie Young, Lions DL #79, was called for roughing the passer, though, and the Bears got a second crack at it from the 1-yard line. This playcall was even more grandly disastrous than the first, though, as an ill-fated sweep from Matt Forte was stymied instantaneously in the backfield. Onside kick failed, and there went the ol’ ballgame.

McCown was really being let down by his coach and his defense. In back-to-back, badass, exhilaratingly extemporaneous outings, he’d forced his team to the very brink of triumph before soggy-cardboard pass D or cerebrally vacuous playcalling had doomed his and his teammates’ chances at glory. And given what he’d shown through one start and two emergency relief appearances, there’s little to suggest that had McCown gotten to start the two games he’d appeared in without starting the game the Bears wouldn’t have won both. At any rate, this intradivisional stumble would cost the Bears dearly.

It certainly didn’t help that the Bears’ next opponent was the defending Super Bowl Champion Baltimore Ravens, but the Bears had a few advantages in this one that the birds didn’t. For one, the 2013 offseason and free agency had wreaked havoc on the Ravens’ starting lineup, with both starting ILBs (the other being Dannell Ellerbe) and both starting safeties (HOFer Ed Reed and Patriot Killer Bernard Pollard) departing along with pass rusher Paul Kruger, center Matt Birk, and perhaps most damaging of all, wide receiver Anquan Boldin. The 2013 Baltimore Ravens were as different a team a year removed from a Lombardi as almost any, especially considering the sharp drop in production suffered by newly minted highest-paid player in the NFL Joe Flacco. One thing they did manage to do was supplement their FB room, which had consisted of only Vonta Leach, with FB of the future Kyle Juszczyk, but other than that, the Ravens offense was worse in every way in 2013. The other advantage the Bears had, other than roster continuity (outside of head coach) was that, with five minutes left in the first quarter and following two Ravens scoring drives, inclement weather forced a nearly two-hour game stoppage while tornado conditions swirled around Chicago. This obviously led to the players getting “cold,” as they say – and no one is better coming onto the field cold than Josh McCown. The Ravens had, of course, had recent experience with overlong pauses in gameplay, as a power outage in the Superdome had forced a halt in action during their Super Bowl victory months nine months earlier, but it should be noted that the purple birds were outscored 25-6 by their foes the 49ers after this lull in action.

The run-blocker beside the field of fog.

After a long intermission, during which I like to imagine Josh McCown provided a reminder to his team that for them to lose during windy conditions at home in the Windy City would be tantamount to an existential crisis, the two teams took the field again. McCown didn’t start out supernovally, but he did get them to the goalline for a field goal and finally got some defensive help from DE David Bass, who did his best J.J. Watt impression by leaping high on the edge to intercept a Joe Flacco flat pass which he returned for a touchdown. 10-10. This was officially a Joe-Josh Joust. Flacco bounced back from the pick and led a scoring drive capped by a Torrey Smith touchdown, and after a punt from the Bears Flacco threw another interception, this one to Jon Bostic, which allowed McCown to drive the Bears into field goal range before the half. 17-13 at the halfway point.

The Ravens got the ball to start the second half, their drive stalling around the Chicago 30-yard line. With pitiless kicking conditions making the likelihood of a long field goal negligible, the offense went for it on 4th and 8. An interesting down and distance. But Flacco was sacked by the backside rush from Cheta Ozougwu, and the Bears took over. They could do nothing with the football, and punted. Baltimore could do nothing with the football themselves on the next drive, so they punted. As the fourth quarter dawned, Trestman began to entrust McCown to toss the ball around again. After hammering the Ravens with Forte and Michael Bush, McCown shot a go-ahead touchdown pass to Forte to go up 20-17 with 10:42 left. The two teams exchanged punts, and after running a bit of time off the clock, the Ravens got the ball back with 4:55 to go.

A late lead and 5 minutes left? This was defensive meltdown time. Baltimore proceeded to mount a ponderous, plodding drive that devoured what remained of regulation before the Bears D finally stiffened, if just enough to forestall an all-time heartbreaking loss, at their own 3-yard line. Justin Tucker then sent the game to overtime.

This game, which had already lasted an eternity, was approaching record-breaking status as overtime broke. Despite winning the toss and getting the ball at their own 36 (!!!), Baltimore could only move the ball 18 yards, and on 4th and 5, in Bears territory, they punted the ball back to the Bears. Were it not for this abject expression of surrender, the Marc Trestman era may have had yet another loss in its unattractive annals for the balladeers to belittle. As it was, the Bears were for once bailed out by another team’s disgraceful deportment, and after a punt of 26 net yards, McCown piloted the Bears straight down the field, using a 43-yard Martellus Bennett catch to set up Robbie Gould’s game-winner from 38 yards out.

Looking back on this game, I had forgotten about the midfield cowardice displayed by John Harbaugh in OT – this wasn’t a terribly memorable game for a non-Bears fan when you discount the weather delay and the utter interminableness of the contest. But being reminded of the overtime punt, I simply had to know how lily-livered this was, so I plugged the numbers into Jon Bois’s proprietary Surrender Index to gauge the pusillanimity. At a soul-rending value of 35.39, Harbaugh’s horrid prostration sits in the 98th percentile of cowardly punts since 1999. Great job, John. Given how long the game had already gone on for, the fact that they were punting to Devin Hester, and the fact that they gained a grand total of 26 net yards for their troubles, it boggles the mind at just how complicit and compliant the Ravens were in tying their own football noose in this game.

Through his four games, McCown had thrown for 5 touchdowns, no interceptions, and 754 yards, good for a pristine 100.0 rating. And he was not even close to his best yet. But despite his out-of-the-blue feats of football dash his defense was sagging. And they plummeted pungently to Earth the following week against St. Louis, who though in the midst of a patented Jeff Fisher 7-9 season were embarking on a strange two-game interlude where they smashed the Colts and Bears back-to-back by 30 and 21 points, respectively. As a Colts fan, I distinctly remember this sequence being spiked by the outrageous explosion of Tavon Austin onto the NFL scene – in these two games he accounted for 443 total yards and 4 touchdowns. There was nothing McCown could do to get his team a W in this one. Even though he had one of the best days of his career – 36-of-47 for 352 yards, two touchdowns and one very permissible interception when the game was out of reach in the last two minutes – the Bears defense stabbed him traitorously in the back yet again. McCown had pulled the Bears to within 6 in the 4th quarter, but the Rams simply plowed through the Bears defense on the next drive to make it 35-21 with three minutes left. Benny Cunningham and Kellen Clemens – yes, really – authored 3 straight plays of double-digit yardage before a nine-yard Cunningham touchdown run cemented it. The defense buckled, and then to join their confederates in disesteem, the special teams did too, with Devin Hester fumbling the ensuing kickoff, recovering the ball at his own 10-yard line. McCown played valiantly on the final meaningful drive, completing four straight passes to reach near midfield, before the ever-underrated Robert Quinn beat Jermon Bushrod immediately off the snap, forcing a McCown fumble that Quinn then returned for the punctuating touchdown – the late-game icing-on-the-victory-cake that Chris Berman would have called the ”Oh by the way…” score.

It got even worse the next week in Minnesota. The Vikings, who were having a dreadful season, made microscopic mincemeat of the Bears on the ground and through the air when they were on offense. The combination of Matt Cassel and Christian Ponder, no great shakes, combined for 283 passing yards between them, while Adrian Peterson and Cordarrelle Patterson added a whopping 246 yards on the ground (211 came from Peterson). Still, McCown, with the help of a 120-yard rushing day from Matt Forte, gave the Vikings everything they could handle, throwing for 355 yards and a pair of scores, with 249 of those yards coming from Alshon Jeffrey’s magnificent receiving day. This game was only the fourth, and to date most recent, game in NFL history featuring multiple players surpassing 200 yards from scrimmage. This should have been a no-doubt-about-it win even despite the massive days from the Cassel-Ponder-Peterson trio, though. McCown piloted the Bears to two third-quarter touchdown drives, both of the scoring plays beautiful and merciless catches from Alshon Jeffrey against a totally overwhelmed Vikings secondary. McCown took the field again in the fourth quarter nursing a three-point lead, but a broken pocket play where he tried to flip the ball forward Brett Favre-style to Forte bounced off a kneepad, ended up in tackle Kyle Long’s hands, and was quickly fumbled away to Minnesota. The defense had a rare moment of greatness on the next series, though, with Danny Trevathan intercepting a bobbled pass and otherwise certain touchdown. But Matt Cassel’s best play on the day came on this same snap, because he channeled his inner Ben Roethlisberger and managed to redirect Trevathan enough to allow another Viking to catch up and start to gang tackle the linebacker. Forte, continuing to hurt the Bears down the stretch, gained almost nothing on the next three snaps, all runs, forcing a punt back to the Vikings. Pinned against their own goalline with under two minutes left and only two timeouts, the Vikings fell to the brink of defeat and faced a 4th and 11, but Jerome Simpson – yeah, the front-flip guy – caught a 20-yard pass to keep the drive moving. Splash plays from John Carlson, Jairus Wright, and another from Simpson got the Vikes into field goal range, which Blair Walsh knocked in. The ensuing drive from Chicago did feature a massive 57-yard return from Devin Hester, but with time enough for only a few plays, Robbie Gould was forced to attempt a 66-yard field goal, which Cordarrelle Patterson returned after it fell short for a few yards. In overtime, McCown continued to play incredibly on his first drive, gaining two first downs in two passes before a drop by Brandon Marshall and a poorly-blocked screen brought up a 3rd-and-11. Here McCown faltered, waiting too long and trusting Jermon Bushrod too much, whose unenviable task it was to block Jared Allen. Allen sacked McCown, who fumbled, but the Bears retained the ball and punted. Spooked by this, after a wild Minnesota drive that saw Walsh miss a 57-yard field goal after his previous attempt had been good but neutralized by an utterly inexcusable facemask penalty on the kick attempt which forced the unspeakable “post-fireworks field goal attempt,” Trestman called five straight Matt Forte runs on the following Bears drive, which brought up a 2nd-and-7 at the Vikings’ 29. Why do I bring up this surely interstitial down? Because it wasn’t interstitial. With more than 4 minutes left in overtime, and a timeout, and with TWO MORE DOWNS to work with on this chain-length’s worth of plays, Marc Trestman actually decided, unbelievably, to settle for a 47-yard field goal attempt. Believably, Gould missed, and the football gods, probably wishing both to stop-up the cascading flood of Weird Football that had burst with diluvial furor upon the Minnesotan field and to spare the Vikings a second tie in two weeks (they’d fought Green Bay to a standstill the week prior), permitted in their infinite mercy the Vikings to drive right down the field and end the afternoon with a blissfully accurate Blair Walsh game-winning field goal.

I could barely believe my eyes when I looked at the box score play log, and then the actual game broadcast, which indicated the game management malpractice committed by Marc Trestman in overtime. It positively boggles the mind. And to borrow a phrase so often unfairly utilized, in this particular instance, I really don’t think there is any explanation for not trying to get more yards. On second down, with two timeouts left and four minutes remaining in overtime, there is no excuse for attempting a 47-yard field goal. The team had turned the ball over once all afternoon on a flukey play and were in no position to need to try putting the ball in the air, risking an interception. There was no aspect of urgency to the play. And there was no reason to think, after gains of 7, 4, 9, 1, and 3 by Forte, that they couldn’t exact even more yards from the flabby Vikings run D. So why the Hell did Trestman think this was a good idea? For the life of me I could not come up with any excuse, whether genuine or whether flimsily invented from the perspective of a self-defensive and probably embarrassed head coach, that could conceivably lend any sort of explanation for kicking a 47-yard field goal on second down with time to spare. I was so bamboozled by the stupefactive inanity of this decision that I decided I needed to scour the internet for Trestman’s postgame comments, secure in my certitude that the beat writers covering this game were intelligent human beings with equal capacity for bamboozlement as I. Thankfully this was easy to find, as the Bears’ own website heads the video of this particular media availability “TRESTMAN EXPLAINS DECISION TO KICK ON SECOND DOWN.” Easy enough. What had Marc to say about this outrageousness? His response was simple: “Once we got inside the 30-yard line, we were gonna kick it.”

What? WHAT??? The 30-yard line was the target? WHY??? Even though I know that NFL head coaches, with their unimaginable work schedules and stress-swamped lives, are not always thinking about how to phrase a dispatch from the press podium with the mot juste of a master conversationalist, this ludicrous answer should have been understood by Marc to be a poor one before he ever uttered it. Regardless, this was insane. Gould’s kick from 47 yards was the same distance that the 1990 Bills had to settle for in their attempt to win Super Bowl XXV – that kick sailed right, going wide and falling off into the dusk along with Scott Norwood’s career. Robbie Gould’s kick did the same. Trestman continued to dig his ditch of ignominy unprompted, though, and noted that another reason they wanted to kick the ball was that they’d gotten the spot of the ball to the middle of the field. Again, you wonder if any of these thoughts had been actually thought-out before they were uttered. Good sir, if it’s second down, you can run whatever kind of play you like on the following snap, and still have the option to “center” the ball on third down!!! Teams do this ALL THE TIME! Worse than all of this, though, even coming as it does as largely an afterthought, is the fact that Trestman actually used his final timeout before the kick – after Gould had taken the field. Indeed, the man iced his own kicker. On second down. With four minutes left. It is in no wise hyperbolic, I think, to say that this rivals Nathaniel Hackett’s special teams hecatomb in Week 1 of 2022 against the Seahawks.

Even though I felt confident that I’d satisfactorily proven the lunacy of Trestman’s illimitably illogical argument for the suitability of this decision to myself, I needed to seek other professionals’ opinions on this, just to make sure others felt the same way about this bizarre decision not holding up under close, or even hazy, scrutiny. Sure enough, one of my favorite early-2010s sports media units, TYT sports, had a special segment dedicated to commemorating the presencelessness of mind demonstrated by Trestman in the December Minnesotan air. “This is the worst decision I’ve ever seen a coach make, and we’ve seen coaches make some terrible decisions. Marc Trestman? Fired, today. Today, today, today, today, today.” Thank you for the affirmations, Ben Mankiewicz. I’m glad the Bears didn’t take your advice, though – how could I have written this series otherwise.

Lost in the foofaraw about the kicking game silliness was the manifestly magical play of Josh McCown. This was someone who two years earlier, in his previous most recent extended playing time, had thrown two touchdowns to four interceptions. He was now up to nine touchdowns, a single interception, 1,461 yards and a passer rating of 103.6. Incredibly, if his season had ended here, he’d have finished 2013 with the sixth-best passer rating. It was an unusually beautiful year for passing across the NFL, due in large part to the two pitilessly efficient seasons posted by Peyton Manning and Nick Foles, who both posted seasonal ratings north of 115 (this has happened only 11 times in NFL history – that two of them would happen in the same year is nuts). Josh McCown’s 2013 season, *if* it ended after the loss in Minnesota, would put him behind Manning, Foles, Phillip Rivers, Aaron Rodgers, and Drew Brees.

But it didn’t end there.

On December 9th, 2013, Josh McCown played perhaps the greatest game a Chicago Bears quarterback had ever played.

V. Royal Procession: Joshua the First

On the night they retired Mike Ditka’s #89 jersey, Iron Mike himself was not the star of the show. He was the rich interlude, the meat of a wonderful sandwich. Don’t get me wrong – Mike Ditka is a stratospherically fantastic personality whose richness of élan actually belies just how great of a coach he was in the 11-year period between 1982 and 1992 as HC of the Chicago Bears. It’s a tragedy he had the misfortune of co-existing with the West Coast 49ers, the Big Blue Wrecking Crew Giants, and the Hogs Redskins – if even one of those semi-dynasty (or fully-blown dynasty in the case of the 49ers) it’s a virtual certainty he would have more than one Super Bowl ring. But Ditka’s Bears – especially the sacrosanct 1985 team, the greatest in NFL history, but also the criminally forgotten ’84 and ’86 teams – are too dense a trove of NFL legendry and living history to be properly chronicled here as an aside in a much different story. But they were good. Mike was good. Incredibly good. Anyway.

On December 9th, 2013, the Bears found themselves at 6-6 with 4 games to go. For any sort of chance at the division or even the playoffs, which they grievously diminished their chances at seizing through a less-valuable out-of-conference win versus Baltimore and with their dismaying tumbles against St. Louis and Minnesota the previous two weeks, they would most likely need to win out.

Winning Out is a scary term in sports. It means “be perfect for the rest of the year.” Only one playoff team per year is ever able to do that (naturally, since ties aren’t a thing in the NFL playoffs), and only a handful of teams each year even go into the playoffs on a winning streak. The previous two Super Bowl Champions, the 2024 Eagles and 2023 Chiefs, were walking shakily on two-game winning streaks going into the postseason, with neither streak featuring eight straight uninterrupted quarters of play from their starters (you can do that when you get to play the fair-weather dalliers that are the late-season Cowboys and Chargers). The previous champs, the ’22 Chiefs, had lost a December game in Cincinnati before embarking on a six-game streak which featured numerous close shaves against the awful Nathaniel Hackett Broncos and Lovie Smith Texans. And a year before that, the 2021 Rams had lost their season finale against hated enemies San Francisco, which they needed to win to steal the 2-seed against eventual postseason opponents Tampa Bay. Those same Tampa Bay Bucs from a year earlier had dropped two straight games 27-24 against LA and Kansas City going into their late bye before facing a procession of football corpses in Minnesota, Atlanta, Detroit and Atlanta again to ride a four-game, offensively godlike streak into the playoffs. None of those teams “had” to win out to make the playoffs, either. The whole reason we play 17, once 16, soon to be 18 games is because that’s how many we feel like we can get away with playing without risking too much injury while getting a long, good look at 32 teams. The NFL is nothing like the other major North American professional sports in this regard: after 82 games in the case of the NBA or NHL, or, unfathomably in comparison to the NFL, 162 in the case of MLB, there’s positively no argument that a team “is” or “isn’t” its record. You can’t say that a team jelled too late if 41 games, almost four dozen contests, separate the beginning of the season from its midpoint. The MLB season is even worse, being two games short of equaling two NBA or NHL seasons, and eight games short of ten individual NFL seasons. As George Will, polarizing former sports scribe and, puzzlingly, occasional PragerU contributor said in an interview for the magnificent Ken Burns Baseball documentary, “You know when the season starts that the best team is going to get beaten a third of the time. The worst team is going to win a third of the time. The argument over 162 games is that middle third.” As fun as it probably is to track baseball teams over 1,500 innings, it is manifestly and diametrically opposite to the NFL. 16 games. There is no margin for error whatsoever. Even a single slip-up can be costly – in fact, of all the hundreds of teams who have started 0-1 since 1940, only 224 have gone on to make the playoffs, or about 30% of all playoff teams. Only 12 Super Bowl Champions lost the first game of their season. At 0-2, the odds begin to close in sharply – only 52 teams have gone on to make the playoffs after dropping their first two, with only three Super Bowl champions counted among them. And when you fall to 0-3, your chances are basically dead, with only six teams since 1938 losing their first trio of contests and making the playoffs. It’s happened once this century, to the very weird 2018 Houston Texans. Only two teams since 1940 have ever made the playoffs after not winning a single one of their first four team games, and one of these was the Buffalo Bills of 1963, who tied one game and still only finished 7-6-1. The 1992 San Diego Chargers are the only team in the history of pro American football to fall to 0-4 and still make their postseason. That should show you how hard it is to dig out of a hole – and how important a four-game stretch is.

At 6-6, and with four games to go, you’d think the 2013 Chicago Bears would have made life easier for themselves than the harrowing improbabilities of teams that drop their first few games make for early-season losers. But incredibly, being at .500 with four games to go carries even worse odds of your team eventually making the playoffs than starting 0-1 does. Think about it. To finish with a winning record, which is often – not always, but often – an understood prerequisite for making the playoffs, you need to win three out of four remaining games, which is always tough to do. If it was easy teams would be finishing 12-4 a whole lot more than they currently do. To be close to assured of a playoff berth (again, not certainly assured, as the 10-6 2012 Bears proved, but close to assured), you need to win all four. Only 157 teams, since we started playing postseason football in 1932, about 21% of all playoff teams, have ever won all four of their final quartet of contests going into the postseason. About two teams a season. This is what Winning Out is, and it is not easy.

Because of their infuriating three-game, 1-2 stretch that saw them win, rather unconvincingly, one interconference game and drop two in-conference ones to terrible opponents, the Bears had basically no breathing room. They would have to defeat the playoff-hopeful Cowboys in Chicago, beat a bad Browns team on the road in December, beat a very good Philadelphia team in Philly, and then beat down the Packers once more at home. Aside from the everlasting disaster that is the Cleveland Browns offense, which would finish 27th in scoring in 2013, the Bears’ opponents were 5th (Dallas), 4th (Philly) and 8th (Green Bay) in scoring O at season’s end. But the Bears themselves? They would finish second. Behind only Peyton Manning’s record-setting Denver offense. And it happened this way in great measure because of the heroism of Josh McCown that cold December night in Soldier Field.

Ultimately, you don’t need all that much to happen to win a game of football. In paucis verbis, all you really need to do is outscore your opponent. That is the only way to win a football game. In slightly more specific terms, you just need the opponent’s defense to be worse than your own offense. And as awful as the Bears defense was and would continue to be, for one night only, Big D’s D played smaller than Chicago’s. And Josh McCown took full advantage. After establishing the run with Matt Forte and Michael Bush before hitting an open Earl Bennett for a score on the opening drive, McCown began to unsympathetically vivisect the Cowboys’ laggard defense, doing a convincing Joe Montana impression that saw him move gracefully inside the pocket, step upfield to avoid pressure when it rarely came close to him, make broken-play completions out of the pass-protection envelope and finally run for an Elway Copter-esque touchdown to make it 14-7. The Cowboys tried to respond with a smattering of tactical Tony Romo throws and DeMarco Murray runs, and after a brief, effective drive that saw Murray carry the ball 5 straight times bookended by two Romo throws and completions to tight ends Gavin Escobar and Jason Witten, the latter for a score, the game was tied. From here, though, the Bears mauled the Cowboys in every which way. They dominated time of possession, holding the ball 23+ minutes to the Cowboys’ 12. They embarked on a gluttonous scoring junket, reeling off five straight scoring drives for a total of 28 unanswered points during which the Cowboys possessed the ball for only 13 plays and gained only 35 yards. The Bears held the ball for over 12 minutes in the third quarter alone, scoring 17 points on 3 drives. The Cowboys had as many scoring drives as the Bears had total negative plays. The Cowboys punted three more times than the Bears. That’s because the Cowboys punted three times, and the Bears did not punt. The sallow imaginings of the Cowboys offense and defense were nothing in comparison to the imaginative, improvisational might of the Josh McCown Career Game, which is a wild sentence to type but is borne out in the viewing of this game.

The Bears scored on every possession until their last, which came with 6 seconds left in the game and the Bears leading 45-28. This was due unquestionably to the blinding brilliance of Josh McCown, and a discombobulatingly pliant Cowboys defense. The Cowboys gave up on average 272 passing yards, 2 passing touchdowns and a ridiculous 31 points in their final five games – all of them against QBs who were not their team’s week 1 starter. Yes – those numbers above are the Cowboys’ passing defense numbers against backup quarterbacks in 2013 (they did face the two-man-band of Nick Foles and Matt Barkley earlier in the season after Michael Vick exited the lineup, performing more admirably by limiting the duo to 209 yards and three interceptions). If we remove the numbers of an organism called “Matt McGloin” from these figures (the Cowboys played the Raiders before their game with Chicago), the numbers skyrocket: over their final four games in 2013, all against former backups thrust into the starting role under center, the Cowboys gave up 1,050 passing yards, the same number of touchdowns (11), and 2 interceptions, allowing opposing passers a supreme passer rating of 109.3. They went 1-3, winning their lone victory 24-23 against the Kirk Cousins Redskins. But Josh McCown was the star of this group, far and away. When the atomic dust that was once the 2013 Cowboys defense settled into the sepulchral turf of Soldier Field, the stats were sanguinary in aspect: 27-of-36 for 348 yards, four touchdowns and no interceptions. That’s through the air. He added three carries for 16 yards and that rushing touchdown, too. Subtract a lone sack for a loss of seven yards and he finished with 357 total yards and five total touchdowns without a turnover. Only 12 quarterbacks, ever, have thrown four touchdowns, ran for another, and accounted for 350+ total yards of offense without turning the ball over. And Josh McCown is one of them. Unbelievably, three of those other 12 quarterbacks are named Drew Brees. Because I lied. There have only been 10 quarterbacks who reached the above marks. Drew Brees just happened to do it three different times (no one else did it more than once). And in typical Brees fashion, whereas the nine other QBs to accomplish this feat went undefeated in their games and won by an average score of 47-27, Brees only went 2-1, despite scoring 46 points in his lone loss (a memorable late-season game against the eventual NFC champions 49ers in 2019, in which a failed 2-point conversion for New Orleans proved the difference in their 2-point, 46-48 loss). Even more fittingly, another quarterback on this list, Ryan Fitzpatrick (the very same) accomplished his 4-1-350-0 Club membership audition against Drew Brees, in another memorable game from week 1 of the 2018 season, which the author of this piece remembers as perhaps the greatest week 1 razor in Eliminator challenge history. Across just 12 separate 4-1-350-0 games in NFL history, Drew Brees was involved in four of them. Remarkable.

But this is about Josh, not Drew. This was a performance from the very stars, which were certainly aligned, and which only the most wholly in-the-zone, fearlessly flow-state-immersed passers have ever accomplished. It could be argued it was the sort of performance that could and should make a head coach think twice about who the long-term starter should be. It certainly is the sort of performance that ought to give a head coach pause about who should get the nod for the rest of the year with three games to go and an on-fire backup clearly outplaying the season’s initial starting QB. At the very least, at the minimum threshold of expectation, it should have given Marc Trestman an easy decision on who to play against the next opponent, the Cleveland Browns.

VI. Dual Monarchy: The Cutler Does It Again

There are several reasons for this. One, we should answer the question that beggars an answer: where was Smokin’ Jay, as he was becoming known around this time, during this interlude of incredible QB play from his erstwhile backup? It turns out that, despite his lack of onfield action, November and December of 2013 were eventful times for the one-time Vanderbilt Commodore from Santa Claus, IN. For one, he publicly disassociated himself from the image of him as a vehement smoker of cigarettes, dealing a grievous blow to early Meme culture operatives who thought he looked like exactly the avatar of apathetic resignation who would have a lonesome dart hanging from his mouth as he trotted off the field. According to ESPN writer Michael C. Wright, when pressed on the subject and asked how many packs a day he smokes on November 18, Cutler said “I don’t smoke at all, bro. I hate cigarettes.” (If you think I’m exaggerating when I say “early meme culture,” the photoshopped image of Cutler with a lit cigarette in his maw originated on Tumblr of all places.) He also had to face the pressure of being briefly profiled on the Daily Herald along with his physical therapist, John McNulty, in an article titled “The man (and machine) behind Cutler’s recovery,” which anointed the wound Cutler suffered on October 20 against the Redskins as “the most talked about groin injury in the NFL.” Quite burdensome stuff, you ask me. On the less trivial side of things, Cutler had been awaiting a glorious, Return-of-the-King-style resumption of royalty on the throne of Bears quarterback for longer than he initially thought he would (with some sources pointing to December 1 as a potential return date for the QB in the days after initially suffering the injury against Detroit which thrust McCown into the role) – but McCown had been already been playing gloriously. There’s only so much gloriousness to go around, and McCown was no Denethor to Cutler’s Aragorn. This should not have been as easy a decision as Marc Trestman ultimately made it out to be. In what has to be one of the most pusillanimous instances of damning-with-faint-praise – and simple understatement – in the history of NFL coachspeak, Trestman voiced the following thoughts in the week leading up to the Browns game, the first featuring a rehabbed Cutler: “Josh has done exactly what we’ve asked him to do – he has performed very, very well as a backup.” That quote per the Chicago Tribune.

Several, perhaps many, unintentional mistakes are made by Trestman in that assessment, but the two worst are 1. The notion that the Bears asked Josh McCown to throw 13 touchdowns to 1 interception over a four-game stretch as starter, and 2. The idea that he played well, as a backup. That unceremonious verbal engraving on Josh McCown’s 2013 season headstone should appall and aggrieve anyone who watched the Joshaissance take glorious form during the Bears’ November and December offensive hot streak. Blech. There might be nothing so unwholesome to connoisseurs of coachspeak as a back-handed, deflective, evasive caveat meant to diminish the doings of a high-performing backup who is about to lose his job. Sure, it’s worth remembering that Cutler only lost his job due to injury, not performance, but you could not have asked for anything better from McCown over this sojourn as The Guy for Chitown.

Regardless, Trestman made his bed. Now he had to sleep in it. On December 15, a cold, windy day epitomizing the rigors of Chicago pro football conditions, the prodigal son returned. Jay Cutler re-entered the starting lineup against the Cleveland Browns, hoping to prove his coach right (who, truth be told, had consistently and unwaveringly, even stubbornly, adhered to the dictum that Jay Cutler was and would continue to be their QB1 whenever he was healthy, saying as much as far back as November 19) and probably also hoping to make a statistically-substantiated good impression on his general manager, Phil Emery, with a looming contract negotiation awaiting him upon the expiry of his existing deal, which was in its last year in 2013. He looked good in his first drive, propelling the Bears offense to a few first downs through the air and causing FOX Sports color commentator Brian Billick to assert “Jay Cutler looks awful comfortable...if they don’t get more pressure on Jay Cutler, he’s gonna cut them up.” Well, either the Browns defense had jerry-rigged their helmets to play the FOX broadcast and sought to disprove Brian Billick, or the broadcaster had just pronounced the least longevity-blessed prognostication of his commentary career, because Jay threw an interception in the endzone to Tashaun Gipson on the very next play. The Jason Campbell-led Browns then punished the Bears defense with a 44-yard wide receiver screen to Greg Little before seeing their drive sputter out and settling for a field goal.

Things were not going well for the Cutlerssance through one drive. On his first drive back from injury replacing a red-hot stand-in, he’d committed a red zone turnover which led to enemy points. It was a 180-degree change from what Josh McCown had done against Dallas the week before. To atone for this, he led a 15-play, 75-yard drive that reached the Cleveland 5 but still only ended in a field goal. It’s better than leading a 15-play, 75-yard drive that ends in a turnover or a punt, but come on. All this did was effectively bring the Bears offense back to zero instead of -3. Campbell threw an interception to cornerback Zack Bowman on the next drive, but Cutler could do nothing with this possession, so they punted. The Browns could do nothing with their next possession, so they punted. This game of touchdown-phobic hot-potato was in need of excitement, the Football Gods decided, and on the ensuing Bears drive, Cutler threw his second interception of the day, again to Tashaun Gipson, who proceeded to careen through the Bears’ futile squad of tackling-drill-needy offensive players down the right sideline for a James Harrison-esque, convoy-aided pick six.

This was as bad a situation as the Cutler-helmed offense could have possibly found itself in. The game was only 10-3, but all of Cleveland’s points had come at Cutler’s turnover-prone expense. The marks that the two Chicago quarterbacks had put up on the seasons now stood at 13 touchdowns apiece, but McCown had thrown only one interception all year – Cutler was up to 10 in nine games. To give you an idea of how prolific Josh McCown had been, and how sloppily giveaway-liable Cutler was, if you combined the two passers’ stats through week 15, you’d have the same number of touchdowns, interceptions, and a touch more yards than Patrick Mahomes ended up with in his 2024 campaign. Josh McCown had basically produced half of a 2024 Patrick Mahomes season, with almost no turnovers, in about a quarter of a season’s worth of play, and he couldn’t keep his job. What a world.

Through four drives, Cutler had a passer rating of 46.79. The day, the Bears’ season, and perhaps the future of Jay Cutler as CHI QB1 looked to be in dire peril, if not irretrievably lost. But after starting 8-of-13 for 104 yards and 2 interceptions, Cutler threw Mr. Nice Guy aside like a crumpled paper cup whose fill of Gatorade has been quaffed and went nuts on the Cleveland pass defense. He proceeded to go 13-of-18 for 161 yards and 3 touchdowns the rest of the afternoon, good for a 139.12 rating, while the rest of the players, both Brown and Bear alike, seemed to self-destruct by turns. The final score was 38-31, Bears. As good as Cutler was after his two terrible turnovers, though, this final score is misleading. The Browns defense actually scored another defensive touchdown, this one at the expense of Martellus Bennett, who fumbled a Cutler completion which was scooped and scored by T.J. Ward, to make it 24-17 Browns heading into the final quarter. This was where Cutler shined, though, leading Chicago to three straight touchdown drives (the final capped with a Michael Bush rushing score). That’s only four touchdowns, though, and the final score would seem to indicate that the Bears scored five. And they did, off a Zack Bowman interception return that was just one yard shorter than his opponent Tashaun Gipson’s scoring stroll earlier in the game. This was a weird, weird game. In fact, it’s one of only 10 games in NFL history featuring two different defensive players who each intercepted multiple passes and took at least one of them to the house. Even more incredibly, these two teams have combined to proffer two such games – the other a 42-0 Browns beatdown of George Halas’s Bears in 1960. Weird! That’s how a game that should have been tied 10-10 at the beginning of the fourth quarter if it were absent of defensive scores instead became 24-17 to start the final stanza. This is the sort of thing that happens, to be blunt about it, when out-of-practice QBs are thrust into the starting role. (Jason Campbell had started for numerous games prior to this one, but, as is the theme of this piece, he was not the Week 1 starter. He wasn’t even the second QB to see action, as he took over for an injured Brian Hoyer, who himself had taken over for an inept Brandon Weeden. But we needn’t delve any more deeply or darkly into the QB genealogy of the post-1999 Browns here.)

8-6. They were 8-6. Halfway from 6-6 to double-digit wins, which should be enough to get you into the playoffs. This would be even better than “getting in,” though – 10-6 would be enough for the NFC North division title in 2013. 2012 was different – even though they got to 10 wins, the almost-always-magic-number, the Bears had fooled around too much in mid-December, dropping two backbreaking one-score in-division games to the Vikings and Packers, which meant they didn’t control their destiny. Thanks to a magical, 2,000-yard-eclipsing performance by the Vikings’ own Purple Jesus, Adrian Peterson, against the Packers in Week 17 of 2012, the Bears missed out on tiebreakers to Minnesota (a 2,000 yard rusher should be the in the playoffs, anyhow). But 10 wins would be enough for a playoff home game this year, a stunning turnaround in circumstance from the previous season. Two. More. Wins.

The road to 10 wins would not be easy. The Bears faced two NFC powerhouses in their final two games, both of whom had proven themselves capable and good at piling up preponderances of points on bad defenses. The first was Philadelphia. After ditching Andy Reid, who was definitely at the end of his coaching usefulness, on New Year’s Eve 2012 (the same day that the Bears fired Lovie Smith), hitched their wagon to Chip Kelly, erstwhile Oregon Ducks head coach who had more or less revolutionized early 2010’s college football offensive philosophy with his hurry-up spread attack. While some more outlandish concepts of the spread offensive scheme had to be mothballed upon his arrival in the NFL, the Kelly hallmark of running as many plays as possible in as short an amount of time as possible had prevailed through his first season with the Eagles, and through this philosophy the Eagles had gone from a team that accrued 5,665 yards in 1,079 plays in 2012 skyrocketed to producing 6,676 yards in 1,054 plays in 2013. They tied with Peyton Manning’s 600-point-club Broncos for the league lead in average yards per play. But this wasn’t all due to Chip Kelly alone. Michael Vick had begun the season as the Eagles’ starter, seizing the QB1 slot with a great preseason (and probably the helpful perception that his dual-threat skillset made him the best suited of the Eagles’ QBs to run Kelly’s offense) after several seasons of serious cooling-off from his heyday with Andy Reid in the latter half of the 2010 season. But after a great Week 1 game against the Redskins – which incidentally I remember watching live and being both astounded and terrified at the pace of the Eagles’ offense during – Vick lost steam quickly, losing his next three starts (including a turnover-free, 460-total-yard-surpassing loss against San Diego) and failing to crack even 15 completions in a game after Week 2. He was then injured in Week 5 against the New York Giants, ceding the job to Nick Foles, who played capably enough in relief to earn Vick an official win as a starter. The job was now Nick Foles’, and he would not give it back.

The insane story of Nick Foles’ career is too long and amazing to be written of in any great detail here, but suffice to say, he came out of absolutely nowhere in 2013, enkindling an efficient offensive inferno each week which when all was said and done amounted to a 27:2 touchdown-to-interception ratio, the second-best ever among qualifying QBs. It’s really difficult to overstate just how near-impossible a ratio of 10:1 or above is to achieve in the NFL, and Nick Foles was well on his way to accomplishing a 13.5:1 ratio. Only one other player in NFL history with qualifying sample size had registered a 13:1 touchdown-to-interception ratio to that point. He was on the Bears and his name was Josh McCown. He had lost his job to a man who had less than a 2:1 such ratio. C’est la vie. But even though Jay Cutler was decidedly not on his way to authoring a passing season for the history books, he had played well enough in his sporadic, oft-interrupted action to set the pregame Eagles-Bears Week 16 line at Eagles -3.0. Since this game was being played in Philadelphia, it means that the handicappers who handle this sort of thing thought it was probably more or less a pick ‘em on a neutral field, maybe with a slight edge to the Eagles. The over-under was 53.5. If you sit down and do the math, you could figure that Vegas thought this game had a good chance of ending up somewhere in the neighborhood of 29-26, Eagles.

Well. That’s not what happened.

The Eagles butchered the Bears in this game. It was the sort of game you just don’t see happen in the NFL very often. Philadelphia inaugurated the incineration of their Chicagoan opponents by sacking Jay Cutler on the third play of the game, taking possession at the Chicago 43-yard line after a pitiful 25-yard punt, and going all 43 yards in 6 plays, finished off with a Riley Cooper touchdown. 7-0 PHI. On the ensuing kickoff, Devin Hester, the greatest return man of all time, fumbled the ball at his own 36 after what could have been a breakaway kick return, giving possession immediately back to Philadelphia. This prompted Cris Collinsworth to muse “Boy, now you have to worry if you’re the Chicago Bears about the avalanche starting.” A prophetic pronouncement. Nick Foles immediately completed a 27-yard pass to Zach Ertz, and four runs later the Eagles were in the endzone again on a LeSean McCoy run up the gut. 14-0 PHI. Eric Weems, a different Chicago returner, who it must be noted was not Devin Hester, decided to take matters into his own hands on the next kickoff, holding his ground in front of Hester and fielding the kick himself, surprising the Windy City Flyer, who almost somersaulted over Weems trying to field the kick. The Bears again went run-run-pass, gaining only 5 yards with some Forte runs before Cutler threw incomplete to bring up 4th and 5. Chicago had to punt again. The Eagles had to go significantly further on their next drive, starting at their own 28-yard line, and Chicago even managed to get the Eagles’ O to a 4th down, but this sticky situation was quickly remedied with an 11-yard LeSean McCoy run on 4th and 1. A few plays later the Eagles were in the endzone again on a Foles-to-Brent Celek touchdown pass. 10 plays, 72 yards, 21-0 PHI. The game was over, for all intents and purposes. The Eagles had scored three offensive touchdowns and Jay Cutler had thrown one pass. It’s not that Jay Cutler and the Bears offense couldn’t come back from a 21-0 deficit – Cutler-led teams scored at least 21 points in 76 of his 153 career games, just one game less than 50% - but the prospect of the appetizingly unredoubtable Bears defense to hold down the Nick Foles/Chip Kelly Eagles enough to let Cutler and Co. work their magic enough to even the odds was an impossibility. Nothing could be done.

The game continued to go as it had been going after the Eagles’ third and essentially game-clinching drive. To look at the drive chart of this game is to peer into baffling, almost unfathomable vistas of cosmic football horror. After surrendering touchdowns on their first three drives, the Bears still remained dedicated to conservative, field position-driven game management. They punted two more times on their following two drives, down three scores, including on a 4th-and-2 at their own 43. Seriously, what is the worst that could conceivably happen in that scenario if you decide to try and pick up a first down? In Trestman’s mind, the answer must have been “something even more awful than going down by more than three scores,” because they punted all the same. This time, fantastically, the defense was able to force a Philadelphia punt through a Nick Foles sack and some poor playcalling by Kelly, but after regaining possession with a chance to make it at least a two-score game the Bears short-circuited in explosive fashion, sauntering all the way to the Eagles’ 19 but taking a combination of sacks and penalties in the successive set of downs that brought up the comedic down-and-distance of 4th and 28 from the Eagles’ 37. For a drive to both reach the enemy’s redzone and still end in a punt is outrageous in extremis, but somehow it happened.

The defense was able to tourniquet the hemorrhaging, somewhat, after they’d taken the 21-0 point-blank bazooka blast in their first three drives, and the offense, dismal as it had been through most of the first half, managed to squeeze in one measly field goal before the half ended – right at the gun, from the Eagles’ 32-yard line. Only five yards upfield from where they’d elected to punt, to be sure, but a field goal nonetheless. Things were looking up again to start the third quarter when the Bears forced a long Eagles drive to conclude in another punt, but the brilliant Philadelphia punt pinned Chicago inside their own 2-yard line. Matt Forte was immediately tackled for a safety to make it 26-3, and the post-free kick Eagles drive resulted in yet another touchdown. 33-3 PHI. The deficit was growing lugubrious in magnitude. Chicago finally got a break after another punt to the Eagles was quickly absolved by a Brent Celek fumble, after which the Bears embarked on a 12-play touchdown drive capped by a Jay Cutler-to-Brandon Marshall scoring strike and a further Earl Bennett 2-point conversion. An interesting time for Trestman to call for the aggressive move of going for 2, considering that getting a 23-point deficit to a 22-point deficit didn’t help them in the mathematics of possessions, but whatever.

That was the last time the Bears would score. Blanking the Bears in the fourth quarter, the Eagles scored three more of their own touchdowns off of such names as Chris Polk, Brandon Boykin, and Bryce Brown (that second guy is a defender, by the way) to make the final score 54-11, Philadelphia. That’s more than enough to cover the 3-point line Vegas had saddled them with. Their 54 points scored also were enough to hit the “over” bet – by themselves. All told, the Eagles outscored the Bears 42-0 in the first and fourth quarters. They also outscored them 12-11 in the second and third. An evil, unholy smackdown, and a truly unusual Scorigami that will probably stand alone as the sole 54-11 final score for a long, long time.

Nothing else really needs to be said about this game. The Eagles were an unstoppable offensive machine in 2013 once Nick Foles entered the starting job: aside from a bizarre two-week intradivisional stretch in late October when the team scored 10 total points in back to back games against Dallas and New York, the Eagles scored at least 24 points in all games featuring Foles. Six of those twelve games saw the team score over 30 points. They also scored 30+ in the first two games with Michael Vick. I thought this was a lot – scoring 30+ in half of your games is not a small accomplishment – and indeed they tied for second-place in most 30-point games (San Francisco also scored 30+ eight times). Denver, in Peyton’s 55 touchdown season, scored over 30 points thirteen times.

9-6 8-7. A win away from a winning season. A loss away from .500. A win, at home, away from the North division title. Win and in. Win – and in.

VII. Warring States: The Beginning of the End

If you weren’t watching football in late December 2013, then you were missing out on some special, special playoff seeding drama. The intrigue of who would be in and who would be out, across both the NFC and AFC, was complex, volatile and adrenalizing. Even though the Bears had dropped a mephitic stinker in Philadelphia on Sunday Night Football the previous week, they still controlled their own destiny going into Week 17 courtesy of their divisional neighbors being the horrible Vikings, the infuriatingly inconsistent Lions, and the hated enemy – the Green Bay Packers.

You could write a longform of similar length, breadth and depth as this one on the 2013 Green Bay Packers. Coming off of a humbling loss in the 2012 Divisional Playoffs, and specifically a pitifully pliable defensive performance against 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick who dog-walked Clay Matthews and company for 444 total yards, 181 (!!!) of them rushing, the Packers were in need of significant upgrades on the side of the ball that tries to stop their opponents from scoring points. It didn’t really happen. They were 24th against the pass, 25th against the run, 24th in total yards and 25th in scoring. They were a comparatively 2000 Baltimore Ravens-ian 22nd in turnovers. By any measure this team was squarely in the bottom quadrant of defenses in 2013. And this is sad, because the team was outstanding on offense. Although their passing touchdowns (25) and interceptions thrown (16) were relatively mild, they managed to eclipse 4,000 yards passing and 2,000 yards rushing, something only 25 teams ever did in a 16-game season. As one of three teams to do this in 2013, it put them among company such as Tom Brady’s Patriots, who were obviously good, and Nick Foles’ Eagles, who we know from our reading were good. But the Packers had one gigantic difference between themselves and their Bostonian/Philadelphian counterparts – they did it with so. many. different. GUYS. For one, they, the ’13 Eagles, and the 2000 Denver Broncos are the only teams to reach 4K/2K without a 3,000 yard passer (Nick Foles cracked 2,800 yards in his 10 games and change). In fact, the 2013 Packers saw four different quarterbacks take meaningful snaps, including our old friend Seneca Wallace and something named Scott Tolzien, who somehow threw for 717 yards in 2.5 games (one a relief appearance). Scott Tolzien! But the 2013 Packers didn’t just have multiple guys throwing passes – they didn’t even have a 1,200 yard rusher. Their leading rusher, rookie Eddie Lacy, managed to get to 1,178 yards, but that’s still 800+ short of the 2,000 threshold. For that, they had to get solid contributions from guys like James Starks (493 yards), rookie Jonathan Franklin (107), wide receiver Randall Cobb (78), backup QB Matt Flynn (61), our boy Scott Tolzien (55), fullback John Kuhn (38), free safety M. D. Jennings (6 yards – perhaps on a fake punt?), and one other person – starting quarterback for the Green Bay Packers, Aaron Charles Rodgers. You know him more as a passer.